In previous articles we talked about the necessity of vision and product validation. In this article we will look at how product discovery and product delivery support the product validation process.

Product discovery helps us to answer the following questions:

- Will users buy the product? Does the product solve a real problem?

(market research, competitive analysis, surveys, etc.) - Can users work out how to use the product?

(prototyping, user testing, user experience, A/B testing) - What are the product’s limitations and obstacles?

(time, money, technology, design, brand, supply chain, resources, knowledge) - Given those limitations, is it feasible to develop the product?

- What are the risks and how we can mitigate them?

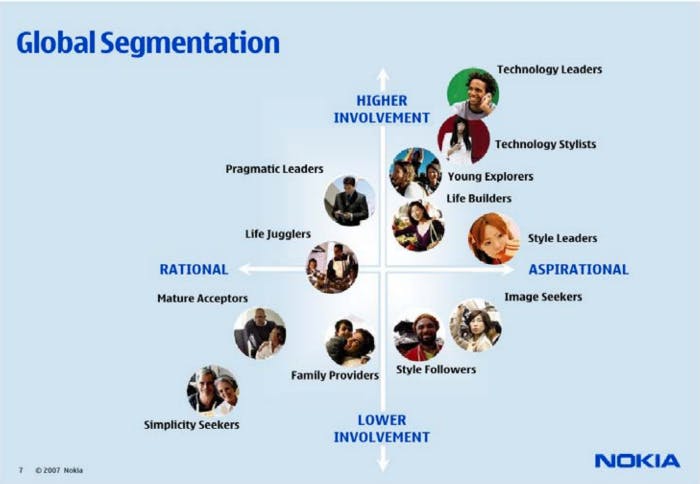

It is important not to get product discovery and market research confused. Market research can be a useful technique during the product discovery phase but it is not a silver bullet. Nokia based their product portfolio on detailed market analysis and a classification of mobile phone users into four categories, each with has several subcategories. They tried to address a specific product series to the needs of each subcategory’s users, but this led to an overwhelming and fractured product portfolio. Because Nokia stopped viewing mobile phone users as a holistic group, it lost its focus. What a relief it was for everybody when the iPhone arrived to point the way forward.

Other techniques

While market research can provide us with useful information, it is not the only available technique and it can sometimes be a bit misleading. Other techniques we can use to expand our idea and understand the context of our target audience include, for example, Jobs To Be Done. I personally like this approach as it enables a company to look at its idea from different perspectives. It also avoids asking the potential users such obvious questions as: would you like this product?

Instead it suggests looking at four different forces that will guide potential clients towards or away from the product. Those forces are: push (a current struggle), pull (a vision of a better life if the struggle is gone), inertia (habits that prevent change), anxiety (fear of change and its impacts).

How to utilise it?

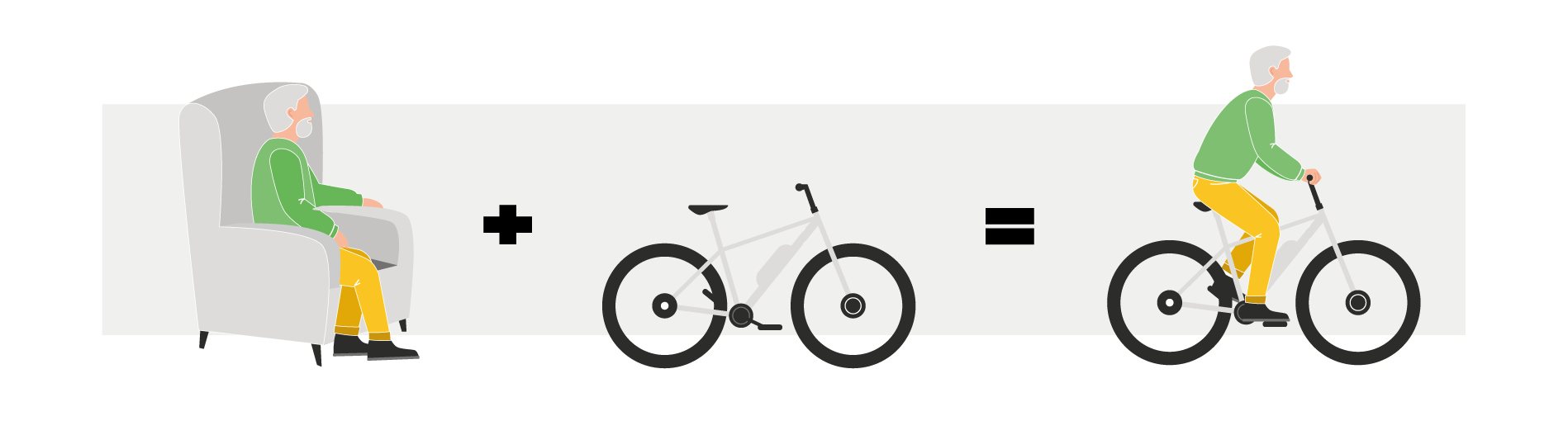

As an example, we might think about a cyclist who has reached a certain age and can no longer afford to go on trips with his younger friends. This is a clear struggle. If we remove this struggle, his life will be better again. The right product in this case could be an e-bike. However, some older cyclists may not feel they need an eBike yet. This is their inertia. If you want to convince them to switch you should show them how much less tired they would be after riding an e-bike and how much they would enjoy it. Anxiety factors might be the price or the limited capacity of the battery. Understanding how these forces interact helps us to answer that original burning question indirectly.

Product Delivery

There is something innately intuitive and seductive about the idea of developing the perfect product on the first attempt. It might seem like an obviously cheaper and faster option. In reality this approach is only cheaper if you know exactly what your clients will use and pay for. Speed is only your friend if you are on the right track. The most expensive way of finding that out is to develop the product and show it to your clients.

The safer, cheaper way is to humbly acknowledge that knowledge comes through experimentation. This is the principle behind Agile development, e.g. Scrum. In every iteration, the most promising ideas are addressed and validated quickly and cheaply. The whole agile development team understands the goal and works creatively to find, within a short time frame (a week or two), a way of implementing a minimal version of the product, which can be used by real users. In later iterations, ideas that prove successful during this validation can then be advanced and improved.

Delivery and discovery go hand in hand. Discovery generates input for delivery, which makes use of it in implementation and validation.

In 2001, the Segway entered the market, hoping to transform transportation as the iPhone had transformed telecommunication. Its founder, Dean Kamen, and its investors had high expectations. But it didn’t succeed. One reason for this, identified in the failure analysis, is that the Segway was designed and developed in isolation, without feedback from its potential users.

In the next article we will look at success traps. Stay tuned.